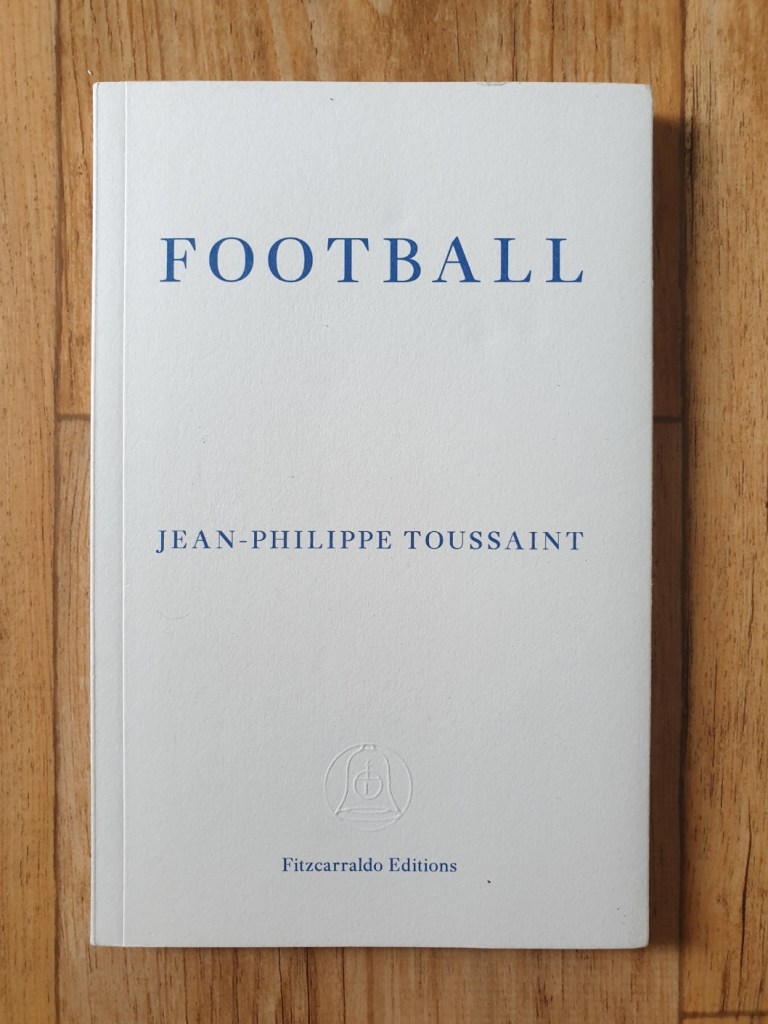

“I cannot dissociate football from dreams and childhood,” Jean-Philippe Toussaint writes in Football. And we, as readers, can be thankful for this. Across eighty-five pages of evocative writing, Toussaint treats us to a selection of lingering vignettes across a life of following football. Framing most of his writing across five World Cups (1998-2014), Toussaint is the aging, harried, and thoughtful everyman who shuffles and scuffs along and against the passing of time.

“This is a book that no one will like, not intellectuals, who aren’t interested in football, or football-lovers, who will find it too intellectual. But I had to write it, I didn’t want to break the fine thread that still connects me to the world.” (pg. 7)

Football begins in 1998, with Toussaint at forty years of age. The year, “though still intimately connected to our lives, to our time, to our flesh and to our history…had accidently sunk its teeth into the edge of the previous century, and inadvertently, found its feet dangling in the past.” In experiencing this transition into middle age, Toussaint recounts early footballing memories. He introduces a recurring motif of the lag and mismatch with time, first in a description of players at the 1970 World Cup, colourised on TV for the first time, leaving their “physical envelope behind and now pursued [their] moves in black and white, leaving behind him the colour of his jersey, which followed him in slight delay.” Despite such vivid memories, he feels a growing detachment with football (realised through his inability to name more than one player of the Belgian national team at the 1998 World Cup). This detachment hints at his general melancholy with life.

“Never have I, as I did in Japan in 2002, sensed such a perfect concordance of times, in which the time of football, reassuring and abstract had, for a month, not substituted but slid, merged into the most enormous gangue of real time, and had made me feel the passing of time like a long protective caress, beneficiary, tutelary, apotropaic.” (pg. 27)

One third of Football is dedicated to Toussaint describing his experiences watching the 2002 World Cup in Japan. Japan is clearly a place that he is comfortable describing in equally rich colour and gloomy substance. Through the neon signs of Shibuya, rain dripping from the ribs of transparent umbrellas, and the convenience culture of 7-Elevens and Family Marts on every other corner, Toussaint effortlessly portrays the buttoned-down culture and colourful, waterlogged kitsch of Japan. The striking scene of a torrential downpour in Yokohama following the end of the World Cup final, where overcautious and polite stewards herd fans with fluorescent truncheons into the Yokohama Metro, is particularly memorable for what it represents: the clashing and melding of cultures at a time when the term ‘globalisation’ was still an unfamiliar concept to many. The 2002 World Cup ushered in an exciting new age for football, represented by Senegal defeating France in the opening match; co-hosts South Korea narrowly missing out on overall third place; European teams flattering to deceive; the raucous partisan Japanese crowds reminding the European and American markets of the UTC+9 time zone…

Like Toussaint does, I must also beg my readers to forgive me for wandering off and dawdling here, for I’m getting to my central point. The 2002 World Cup was a formative footballing moment for many of us, that “perfect concordance of times” that in memory becomes melancholic and slightly discordant. And this is the take-away from Football: thatwhere there was once colour will soon fade and become monotone. As Toussaint tells us plainly, “I am pretending to write about football, but I am writing, as always, about the passing of time.”

Throughout less-than-satisfying experiences attending and watching subsequent World Cups, Toussaint wrestles with his disaffection until difficult times in 2014 force him to face another concordance—that of professional crisis and the absence of existential meaning. The passage where Toussaint struggles with the buffer and lag in a paid stream of the Argentina v Netherlands semi-final in the 2014 World Cup illustrates him as a man also discordant with technology, and with technology being a gauge of progress, he becomes further displaced in modern times. Another storm and downpour frames this closing to Football, providing a form of cleansing and reconciliation to finding some contentment in his existential lag.

“A cycle was coming to an end, leaving me empty and lost. I experienced a crisis, a fleeting moment of doubt, uncertainty and dejection, which lead me to inquire into the meaning of my life and my commitment to literature” (pg. 63)

Toussaint’s claim that everything contained within Football will appeal to nobody is somehow appealing and endearing. The terse title may already put off pontificating intellectuals and raging tribalists (who both think they don’t need to be told about football) who may not commonly seek the middle ground with the each other. Toussaint appeals to those who are fed up, overindulged, and out of time with football, and those who recognise that football isa middle ground, sitting in light and shadow, that we merely dip in and out of as one means to live, rather than an end to live.

Yet don’t misunderstand—Football is a work of philosophic literature from Toussaint, an established literary intellectual of the nouveau nouveau roman (‘new new novel’) school that pushes narrative experimentation and fragmentation in prose writing. As such, Football can be analysed for what underlies the words beyond their surface meaning (and there will be times when Toussaint’s flair for expression will prompt you to consult a dictionary). Toussaint’s writing style of parataxis and cumulative build-up befits his melancholic recollection and a harried search for a place in time (a shoutout is due here to Shaun Whiteside for his sublime translation). Yet despite Football’s intellectual bent, a familiarity with literature isn’t needed for us to understand what Toussaint is telling us.

For although the experiential knowledge gained with the privilege of attending one World Cup, let alone three, is beyond the means of most of us, the spiritual journey of falling in and out with the world game as fortune and time dictates, is familiar. It is above literary pretensions. One of the many things that the COVID-19 pandemic taught us is that sport is inextricably linked with culture and society, and acts as an identity-forming crutch for so many who are marginalised and ignored by society at large. The belaying rope snaps hard against our falling out, but we are inevitably pulled back toward the safety of midweek and weekend fixtures in due time. We keenly know the disenfranchisement of being ‘apart from the main’, and existing in that space where the lack of colour means a lack of meaning. Yet when we do return from that emptiness, we are forever trying to chase back the time lost.

“At every hour of the day, whether I am walking on the beach or strolling up the path through the scrubland to the old tower, whether I’m swimming in the sea or reading in the little garden, when I’m sleeping, a tireless process of ripening is still at work.” (pg. 67)

Toussaint offers this ‘passing of time’ in Football, but in 2025 we can recognise not just the passing of time, but the compression of time with jam-packed fixtures and never-ending content instantly vying for our attention, resulting in the acceleration of time making games, moments, and player careers highly perishable and easily forgettable. Would Toussaint consider his struggles with technology quaint in current times, when we continue to pay top dollar for subscriptions and streams that still buffer and lag despite greater bandwidth to deliver gigabytes of content on-demand? Despite the distortion of our time so that we may more readily consume the increasingly inconsequential, we, like Toussaint, fall into that melancholic middle ground where it takes all of our attention and energy to keep up, only to remain perpetually off the pace.

So, along with Toussaint, we drift back to our memories and to that ‘perfect concordance of times’ to give us spiritual relief. A wisp of Toussaint’s concordance lies in the common denominator between Roberto Carlos, Shinji Ono, Carsten Jancker, and Pierluigi Collina. Such subtle renderings of time and place make Football sparkle. We desire our own “perfect concordance of times” again, like the return of a cleansing storm. Football is Toussaint’s connective tissue with the world. In a football context, what could be more relatable?

“Football does not age well, it is a diamond that only shines brightly today.” (pg. 24)

Football as a means to ‘life sketch’ is an acclaimed substratum of writing, the brilliance of which is shown in works such as Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch and Gary Imlach’s My Father and Other Working Class Football Heroes. The rich base of reporting and storytelling constantly broadens and deepens. Toussaint’s Football can be added to this. And when ninety minutes seems such a long time to do anything nowadays, you won’t regret the ninety minutes spent reading Football. So, embrace the lag, throw yourself into shadow, silence, and solitude as Toussaint does, and let the time pass without raging against it.

Note: This Fitzcarraldo Editions print of Football also contains Toussaint’s essay ‘Zidane’s Melancholy’, which is not reviewed in this entry.

STARS: 4.5/5

UNDER 20: A hidden work of football literary brilliance that in warning off the wilfully scornful, warms to discerning and disaffected fans.

FULL-TIME SCORE: When the majority of the crowd have left the stadium to beat the traffic before the closing of an uneventful 0-0 draw, the unknown substitute comes on to provide a dazzling cameo, long remembered by those who stayed behind.

RELATED READING: Fever Pitch by Nick Hornby (1992)