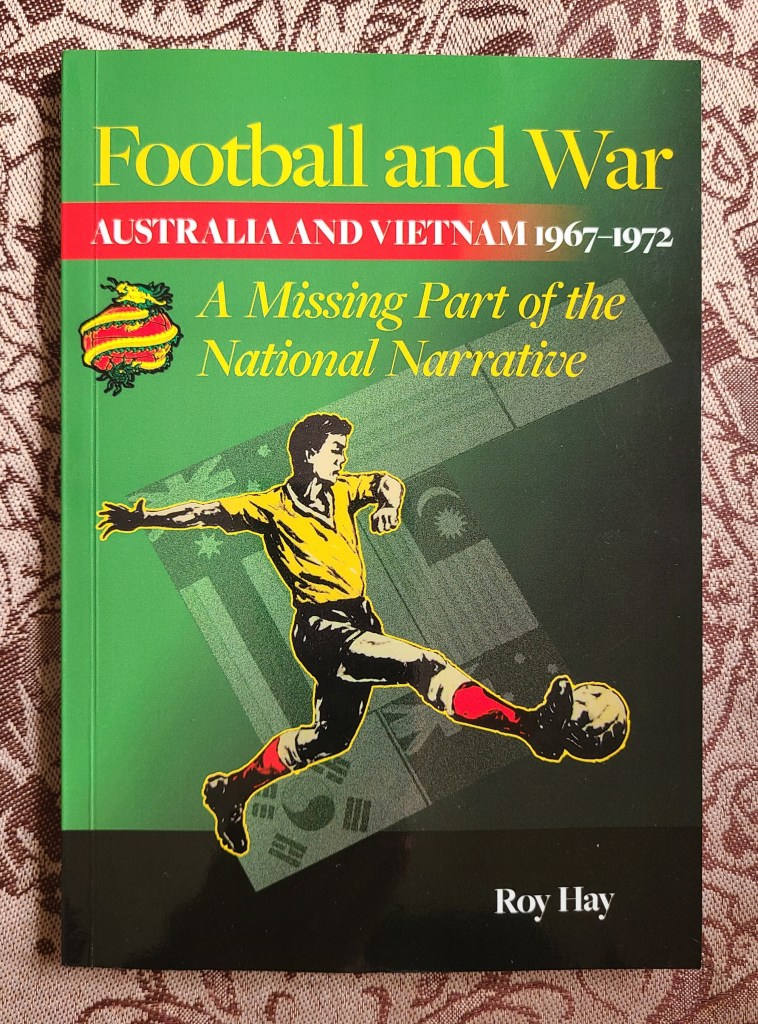

Sometimes I find a very niche football book on a second-hand book shelf. When I do, I wonder if it would make suitable fodder for review. When I saw Football and War: Australia and Vietnam 1967-1972 by Roy Hay nestled tightly between two hardbacks and barely visible in the shadow of the bowing shelf above it, I knew that it deserved to be given the light of day.

The book—its cover coloured with that familiar Australian sport green of Pantone 348C—possesses a frailty suggestive of self-publishing. It’s a wafer of a book that seeks to describe a forgotten part of national lore in a sport that has fought inwards on itself in civil war as much as it has fought outwards on other codes for recognition in Australia. Football and War—now this was niche, and eminently reviewable. It’s time to put on my green and gold anorak.

Football and War by Roy Hay (one of Australia’s most well-respected and eminent footballing and sporting historians, and Football Australia 2025 Hall of Fame inductee alongside Tim Cahill and Sharon Black) is about the Australian national team’s trips to south-east Asia from 1967-1972 during the height of the Vietnam War. The team played a number of Asian confederacy teams in this span of time, and played many of the games in Saigon as a means for the Australian military in Vietnam “to use football as a vehicle to bridge the cultural divide between themselves and the local population”.

Although the veracity of the trips’ diplomatic function and success are under question in Football and War, through Hay’s thorough research, he portrays a portentous nexus of tour success, embedded team camaraderie, and trial by fire across five years that contributed to the team’s qualification for the 1974 World Cup and helped to inch the footballing needle closer into Australian popular consciousness. The 1967-72 period was one of great significance for the national team, and deserving of the lofty appellation of ‘the missing part of the national narrative’.

“The Australian military in Vietnam had begun to use football as a vehicle to bridge the cultural divide between themselves and the local population. So, the Australian involvement in the tournament could build on that. The conditions in Saigon in 1967 were not conducive to soccer diplomacy, however” (pg. 20)

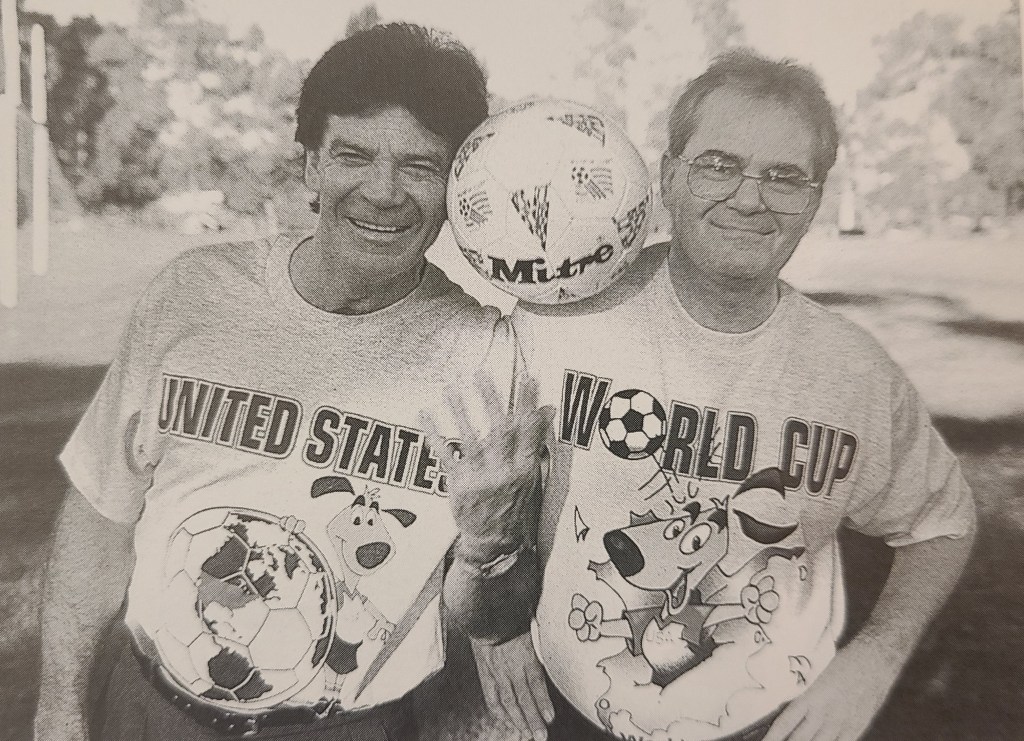

Hay explores several elements of this now-found, still-unheralded, and long dusted-over missing part in precise detail. Aside from Australia’s glut of wins against other national teams (South Vietnam, South Korea, and Singapore, among others) and local teams (Kowloon Bus Company, anyone?) that led to much fanfare and esprit de corps between players, administrators, and journalists, the players were playing alongside very clear and present dangers on the high-grass pitches of Vietnam. Hay relates anecdotes of partisan local crowds cheering Australia on, and beer-swilling Australian servicemen on-leave cheering the team on even louder; Vietcong intentions of bombing a building where the Australian team was staying; and how amongst the sound of gunfire and artillery in the area, the players were deeply aware of Vietcong match spectators who enjoyed the games enough to lay down their guns for ninety minutes.

“…two Vietcong carrying explosives had been captured half a block from the hotel. Under torture, they said that they intended to blow up the South Koreans who were billeted a floor below the Australian soccer players in the Golden Building” (pg. 22)

Hay thoroughly analyses the costs of the tours, from both political and financial standpoints. He draws upon reliable, first-hand sources to add weight to his observations. One of these sources was the former PM, the late Malcolm Fraser, who combed through his personal archives for a diplomatic basis for the 1967-72 trips. The fascinating player and staff anecdotes and political intrigue aside, however, Football and War reads absolutely as dry as chips. There is a cerebral detachment from the topic that is off-putting in places. Hay’s professorial tone reads like an annual report or a Wikipedia entry, rather than a narrative history. The short length of Football and War facilitates an expediency that allows for brief analyses that provide little connective tissue between chapters. As such, the book is an easy read, but not necessarily a read to remember. This is an important point for me.

As a millennial born a full ten years after the Fall of Saigon, my popular consciousness of the Vietnam War has been bounded by Hollywood portrayals, its zeitgeist of protest music, and a brief bus trip through areas of Hội An. Closer to my cultural and national identity, Cold Chisel’s ‘Khe Sanh’, the 1979 film The Odd Angry Shot, and my father’s vague re-telling of his birthday possibly being plucked out for national service, have informed my cultural understanding of Australia’s role in the Vietnam War.I’m probably not alone in knowing more about Australia’s efforts in WWI (Gallipoli) and WW2 (Kokoda Trail) than its role in the Vietnam War. I recognise this as a personal shortcoming—not striving to find out more about events that deeply affected the lives of Baby Boomers; in whose ranks I can count my parents, uncles, and aunts.

This is why I found Football and War to be a bridge for my deeper understanding of the Vietnam War from a cultural identity context. The intersections of conflict, politics, sport, and society that occurred during the Australian national team’s trips to Asia across 1967-1972 offer up a grand opportunity for a longer historical treatment in print. Football and War, in its brevity, perhaps passes up the chance to bring the remarkable story of the 1967-1972 tours to a public that responded so well to Johnny Warren’s Sheilas, Wogs, and Poofters in 2002. Interest certainly exists in the 1967-1972 tours. The Socceroos website has a few articles and interviews about the tours, and articles by Richard Cooke and Les Murray can still be read online. The following extract, from Murray’s article, describes the riot after the Socceroos defeated South Vietnam:

“When the team finally left the stadium, its bus was pelted with rocks. Windows were broken. Young men representing Australia, part-time footballers who worked as tailors, used car salesmen and milkmen, were in fear for their lives. Johnny Warren spoke to me about this event a lot. He was very proud whenever he did. He was proud of ‘the boys’, the sacrifices they made and the spirit they founded. He even suggested that the Socceroos of 1967 had a right to march in the Anzac Day parades, and he had a point.”

From this perspective, the events of Football and War become as much a ‘missing part of the national narrative’ in an Australian historical and cultural context, as in a footballing context. With the 1967-72 tour members yet to receive the right to march in Anzac Day parades, a 2021 article by Chris Curulli sums up how the 1967 tour was consistent with the cultural values that still hold strong today: mateship, persistence, endurance, determination, and sacrifice. Not picking up a weapon should not preclude the members of the 1967-72 tours from reflecting these qualities.

“The Australians played 10 games on that tour and won them all. The camaraderie in the face of adversity was an important element in the mindset that eventually helped the Australians qualify for the World Cup in 1974” (pg. 42)

Describing something as ‘admirable’ can come across as snide. When I call Hay’s work in Football and War here as ‘admirable’, I in no way mean it to be snide. I use admirable here in the sense that Hay has produced a work of merit within the form and length he has confined himself within. But where the brief taste inspires fascination, so it also easily leaves the palate dry. We look to the past to explain the present, and after being so blissfully drunk on the analysis of our drought-breaking 2006 World Cup qualification, similar analysis and extended treatment should be afforded to the pioneering efforts of the 1967-72 tours to instill that teak-like resilience into the latter-day players. Football and War’s brevity hints at a much greater potential left restrained.

In uncovering something that has been ‘missing’ from public attention or inclusion in national sporting lore, Football and War briefly takes the story out of the archives rather than letting it breathe long enough to be well-remembered.

STARS: 3.5/5

UNDER 20: A rigorous retrospective of pioneering Socceroos who brought some cooling footballing diplomacy to the raging heat of the Vietnam War.

FULL-TIME SCORE: The quality of players on the pitch notwithstanding, there is not much to take away from the 0-0 draw that leaves supporters ruing missed opportunities.

RELATED READING: Sheilas, Wogs and Poofters by Johnny Warren (2002); A History of Football in Australia by Roy Hay and Bill Murray (2016)