“You don’t have to understand. If I’d wanted you to understand I would have explained it better.” This well-known phrase of Cruyff’s, originally spoken in relation to contract negotiations to become Holland’s national coach before the 1994 World Cup, is often wheeled out to remind everyone how obstinate and single-minded Johan Cruyff was when it came to his principles. This phrase showed Cruyff—the visionary, the sublime tactician, and purveyor of beautiful football—at his indomitable best.

However, this phrase also reflects how intensely private Cruyff was of his personal affairs, and how unwilling he was to offer up a softer side of himself to journalists. Cruyff’s sad passing in 2016 ensured that little was left in the way of an autobiography (aside from the disappointing My Turn published posthumously in 2016), leaving the best accounts of his life’s work to the journalists who followed him closely. The best of these is undoubtedly Ajax, Barcelona, Cruyff by Dutch journalists Frits Barend and Henk van Dorp. In this book, the many sides of Cruyff are laid bare in a series of fascinating interviews with the two journalists over a period of 25 years. The end result is not only a compelling, finely layered, and insightful character study, but also a ground-breaking piece of footballing long-form that straddled the line between traditional biography and cultured essay.

“I’ve been called a tactical genius. I’ve trained the first team, the C-team and also the youth teams. And practice has convinced me you don’t need a diploma for that. I only talk about technique and tactics. If Ajax has to train for physical condition, I just don’t join in. When I was young, I also hated running in the woods.” (pg. 35)

Cruyff speaking to ‘Vrij Nederland’ in March 1981 (pg. 35)

The interviews and articles follow Cruyff as player through his salad days at Ajax and Barcelona in the 1970s, and finishes with the end of his coaching stint at Barcelona in the mid-1990s. The content of specific interviews is wide-ranging, and rarely static. The dialogue between Barend, van Dorp, and Cruyff makes for stirring reading, and Cruyff’s Barcelona interviews (as coach) help to pin down many facets of Cruyff’s character. Gold dust lies between the footballing matters—Cruyff is often prompted on family life, religion and philosophy, and he mostly replies candidly. Elsewhere he shows his tempestuousness and exasperation, resulting in stand-offs between him and the journalists. Cruyff truly flows and rages like a river moving through rapids. His answers are often incomprehensible (even to the journalists) and evasive, but herein lies the humour and tension.

Ajax, Barcelona, Cruyff is not a typical football biography. In format alone, it demands of the reader a basic knowledge of both Dutch footballing dominance in the 1970s and Cruyff’s footballing and coaching exploits. In the interests of providing context, the translators for this English edition (David Winner and Lex van Dam) include magazine and newspaper articles that did not feature in the Dutch edition. These additions are indispensable in painting a picture of Cruyff in the 1960s and 1970s. The very specific nature of the interviews especially caters to the football fan look wistfully at football in the 1980s and 1990s. As Barcelona coach, Cruyff waxes lyrical on the future of young Dutch tyros Aron Winter and Richard Witschge; he laments at the loss of Ronald Koeman and the laziness of Hristo Stoickhov; and he reflects upon his foreign contingent at Barcelona of Popescu, Kodro, Luis Figo, and Hagi post-Romario. The nostalgia trip is real.

“When you are 4-0 ahead with 10 minutes to go, it’s better to hit the post a couple of times so the crowd can go “oooh” and “aaaah” because if it’s 5-0 nil, it’s only for the score, it doesn’t affect the result.”

Cruyff on ‘Barend and Van Dorp’ in April 1997 on how football should be played beautifully (pg. 218)

Although Ajax, Barcelona, Cruyff was first published in 1997, readers will appreciate this portrait of Cruyff more so than his recent autobiography My Turn. The transcripts in Ajax, Barcelona, Cruyff show a dedicated family man (“I’m my daughter’s father”) who picks up the children from school; a philosopher who discusses social affairs and the existence of God; a man who sticks by his footballing principles even in the face of greater opportunity (“I could never work for AS Roma. They have a running track around their pitch. That’s the worst thing there is”); a maverick who never admits he is wrong (“If there was [a time I was wrong], I would never talk about it, never. I would put it away. That’s part of my character”); and a retired player-cum-coach who loves to get stuck in on the training pitch (“There are obviously a thousand and one problems a day here. My only distraction is the one and a half hours I’m on the pitch”). Ajax, Barcelona, Cruyff is a warts and all depiction of Cruyff—it is far-removed from the self-serving and arrogant language of My Turn.

“Last Friday, Cruyff was given an ultimatum. ‘Why an ultimatum when we’re still in the middle of negotiations?’ Cruyff thought. How was he supposed to react to the combination of faxes from the KNVB lawyer Mr Utermark and from Staatsen, bearing in mind that it’s impossible to insult Cruyff more than by giving him an ultimatum. Cruyff might not be arrogant, but he happens to be the Sinatra of football trainers and it remains very Dutch to say that Cruyff shouldn’t think he is Cruyff. Think about it!”

On Cruyff’s contract negotiations with the KNVB, in ‘Nieuwe Revu’ in December 1993 (pg. 164)

The translation is seemingly faithful to the turn of phrase used by Cruyff and the interviewers. Some readers my find the translation jarring and inaccurate, yet knowing that Cruyff had a very distinctive speaking style (“Cruyff can be enigmatic and elliptical to the point of incomprehensibility”) it seems hardly fair to criticise the translation. As previously stated, the articles are very selective in time frame and context, and some may be disappointed that there is almost zero mention of his career in the United States to claw back his fortune following his disastrous decision to invest in a pig farming venture. This may be due to the journalists’ overt criticism of football in the US (“in the United States, where football or ‘soccer’, never was and never will be anything, Cruyff can walk the streets without being disturbed”). Where Cruyff describes his US experience as a defining time for his career and life in My Turn, Barend and van Dorp completely overlook this in Ajax, Barcelona, Cruyff. Cruyff’s experience in the US deserves greater coverage, especially in long form. It is therefore a disappointing omission from an otherwise great book.

There will never be a character in the football world as enigmatic and forward-thinking as Johan Cruyff. Although much is written about his footballing ‘vision’, his tactics, and his immense contribution to the game that still resonates in the present day, there is less written about his life in sum—especially when Cruyff himself famously refused to dwell on his past. Ajax, Barcelona, Cruyff is therefore an invaluable treasure for the footballing community. Despite its unorthodox style and it being twenty years since it was first published, this book is still the most objective and rounded impression of this football revolutionary and bona fide legend.

HIGHLIGHTED PASSAGE

“We’ve listened to a lot of tapes of you. There’s a lot of verbal battles, because you always want to talk rubbish and then we say, Johan, be clear. And then you say: Let me talk, let me explain. As seen through out interviews, your life is one big war. You’ve been active for about 35 years in professional football, and for almost 35 years it’s been a war. Why is that?” Cruyff: “War? Arguments!”

Cruyff on his so-called ‘war’, on ‘Barend and Van Dorp’ in April 1997 (pg. 248)

STARS: 4.5/5

UNDER 20: A series of revealing articles and interviews with Johan Cruyff contribute to a stunning character study of the legend.

FULL-TIME SCORE: The indomitable coach adopts his trademark fluid, attacking display to great effect in a fully-fledged team performance resulting in a 4-0 win (with a last-minute shot against the bar to make the crowd go oooh and aaaah).

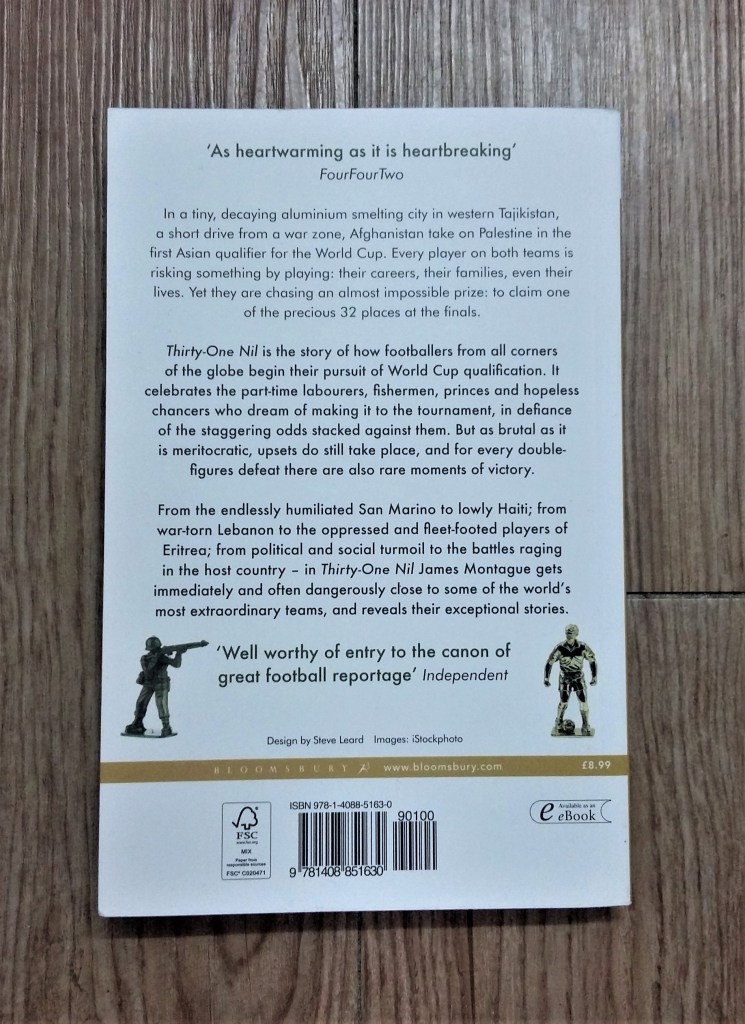

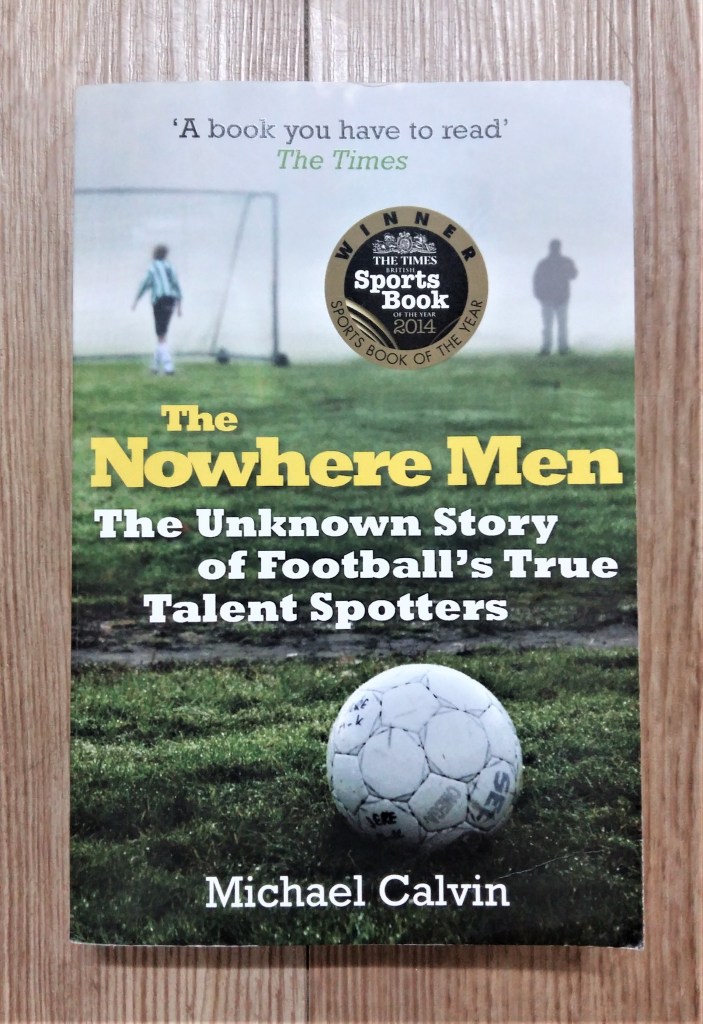

RELATED READING: Brilliant Orange: The Neurotic Genius of Dutch Football by David Winner (2000); My Turn by Johan Cruyff (2016)